Tsongkhapa’s ‘Three Principal Aspects of the Path’

November 3, 2017

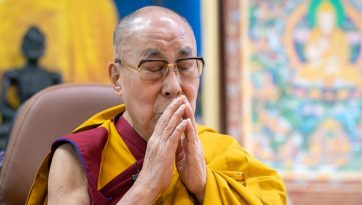

Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – The announcement that His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s teachings today were open to the public was made at relatively short notice. Nevertheless, more than 4000 people gathered at the Tsuglagkhang, the Main Tibetan temple, to hear him. Once he had taken his seat on the throne, he explained that yesterday saw the inauguration of a new school at Namgyal Monastery. Young monks who up to now have been attending TCV School will now be able to receive a general education within their monastery.

Among supporters of the project were 45 Italians and 130 Vietnamese, students of the Abbot, Thomthog Rinpoche. In response to their request, His Holiness decided to teach Je Tsongkhapa’s ‘Three Principal Aspects of the Path’. He explained that they, as well as parents of young students at the Monastery from Mön, Arunachal Pradesh and Tibetans visiting from Tibet, were the main disciples for today’s discourse.

After recitations of the ‘Heart Sutra’ in Italian and Tibetan His Holiness remarked that as is his custom he would first make clear the importance of engaging in spiritual practice and what Buddhism is about.

“Here in the 21st century we’ve seen extensive material development which has resulted in better medical facilities, thriving economies, and greatly enhanced communications. People’s lives have become easier. Living standards have risen. Three generations ago many thought that such material progress would meet all our needs. However, it has also given rise to problems, such as the refinement of weapons whose only purpose is to harm and kill.

“The huge gap between rich and poor in many parts of the world is a result of material development without regard for inner values. Even religion is used by some to see others in terms of ‘us’ and ‘them’—an unthinkable contradiction since religion is supposed to be about fostering love and affection. For example, people in Burma are followers of the Buddha’s compassionate teachings and yet we see Buddhists attacking Muslims. Elsewhere, there are conflicts between Sunnis and Shias—fellow Muslims and between Protestants and Catholics despite their being fellow Christians.

“We are all at peace here, but elsewhere in the world people and killing each other and children are dying of starvation. We all face the problems of birth, aging, sickness and death and yet we neglect others’ needs because of our lack of inner values. Although we pray for everyone’s benefit, we would be better to do something practical to help them.

“The source of our trouble is that our minds are unruly. We can counter that by developing a warm heart. We need to effect an inner transformation, to understand that love and affection are a real source of joy. As human beings we are social animals, dependent on each other. It’s important to be warm-hearted rather than selfish. We’ll be less sick, live longer and have more friends here and now. Therefore, we must try to incorporate love and compassion into our education programs.

“Material development ensures sensory gratification, but its pleasures are short-lived when compared to the benefits of a calm mind and a warm heart. What disturb our peace of mind are emotions like anger, desire, attachment and jealousy. So it’s helpful to understand the various factors that give rise to such destructive emotions and how to tackle them. Just as it’s good to be physically fit, it’s good to be mentally fit too.”

His Holiness mentioned that where Judeo-Christian and Muslim traditions focus on faith in a creator god, many Indian spiritual traditions focus on concentration (shamatha) and insight (vipashyana) in relation to the mind. He noted that whereas the Vietnamese have traditionally been Buddhist, followers of the Nalanda tradition, Italians, who are more commonly Christian, are interested and attracted to Buddhism because it is based on reason and logic.

His Holiness remarked that when Shantarakshita introduced Buddhism to Tibet in the 8th century, he also demonstrated how to study through reading and listening, reflection and meditation. He introduced the Middle Way School of philosophy and the use of reason and logic to understand it. He and his principal disciple, Kamalashila, taught how to deal with emotions and effect a transformation within.

“Buddhists believe neither in a creator god, nor in an independently existent self,” His Holiness explained. “In the first turning of the wheel of dharma, his first teaching, the Buddha referred to causality and the selflessness of persons. In the second turning, he also indicated the selflessness of phenomena, their lack of intrinsic existence. What he taught during the third turning of the wheel became the basis of the Mind Only School of thought.

“We find different philosophical positions within Buddhism because of people’s different dispositions. Within Tibetan Buddhism we have the older and the newer translations, the Nyingma, as well as the Kagyu, Sakya and Kadampa traditions. Unfortunately, there was sectarianism in Tibet, but since we all rely on the same classic texts, we should honour and respect each other’s traditions.

“The text I’m going to teach today is by Je Tsongkhapa who trained with masters of both the older and newer traditions. He studied the treatises of the Six Ornaments and Two Sublime Masters thoroughly, saw what he learned as instructions and put them into practice. He enjoined his disciples not to adopt half-measures, but to study thoroughly in detail as he had done. Just as Nagarjuna’s greatness is revealed in his writings, Je Tsongkhapa’s exemplary clarity is exhibited in his.

“The Three Principal Aspects of the Path was written for Tsakho Ngawang Drakpa,

instructing him how to practise the Dharma. Je Tsongkhapa told him, ‘If you follow my words, I’ll guide in all your lives and when I manifest enlightenment, I’ll teach you first.’

His Holiness mentioned receiving explanations of this text from Tagdrak Rinpoche, Ling Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche. In his account of it he remarked that if a spiritual master is going to tame the minds of others, he must first tame his own by engaging in the three trainings of ethics, concentration and wisdom. He touched on the need to understand true cessation and how realizing selflessness leads to it. He noted that when you do not for an instant wish for the pleasures of cyclic existence, but day and night remain intent on liberation, you have produced a determination to be free—first of the three principal aspects of the path.

His Holiness remarked that depending on how you read them, verses 7 and 8 can be taken as reinforcing the determination to be free as well as stimulating the generation of the mind of enlightenment—bodhichitta.

Swept by the current of the four powerful rivers,

Tied by strong bonds of actions, so hard to undo,

Caught in the iron net of self-centredness,

Completely enveloped by the darkness of ignorance,

Born and reborn in boundless cyclic existence,

Ceaselessly tormented by the three miseries

All beings, your mothers, are in this condition.

Think of them and generate the mind of enlightenment.

He stressed that once you understand that liberation or nirvana is possible you aspire to achieve it. Then, understanding that others too can be free from suffering, you give rise to the aspiration for enlightenment for their sake.

His Holiness further clarified that even though you may have accomplished the determination to be free and the mind of enlightenment, without wisdom, the realization of emptiness, you cannot cut the root of cyclic existence. He observed that in advising, ‘Therefore, strive to understand dependent arising,’ Tsongkhapa is commending the subtle explanation of the Middle Way Consequentialists that things exist only by way of designation.

Judging that the profundity of the Buddha’s teaching is expressed through the practice of the awakening mind of bodhichitta, His Holiness lead the audience through a simple ceremony for generating that awakening mind, concluding with the verse:

May the precious and supreme bodhichitta

Arise in those in whom it has not yet arisen;

And where it has arisen may it not decrease

But ever increase more and more.