‘The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas’ and ‘Commentary on Valid Cognition’

December 24, 2018

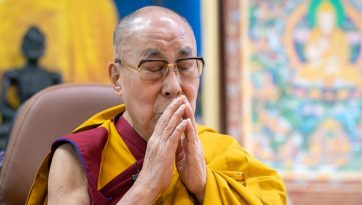

Bodhgaya, Bihar, India – Leaving his quarters on top of Gaden Phelgyeling Monastery this morning, His Holiness the Dalai Lama visited the Monastery Temple. He paid his respects before the existing images of enlightenment and consecrated more than 200 freshly prepared statues of the Buddha. Walking to the Kalachakra Pavilion from the Monastery he waved to well-wishers gathered on the road. Within the Kalachakra Ground he continued to greet friends crowding the barricades and waved to others in the distance as he made his way to the stage. Almost 15,000 people were congregated on the covered ground, including more than 7000 monks, 1250 nuns, 1555 Geshes and Abbots, 15 Geshemas, and 1665 visitors from 70 countries other than India.

Once His Holiness had taken his seat on the throne a group of Theravada monks recited the ‘Mangala Sutta’ in Pali. They were followed by a group of schoolgirls from the local Maitreya School, who chanted the ‘Heart Sutra’ in clear Sanskrit, then another group who chanted it again in Chinese.

“Here we are gathered at this extraordinary place of Bodhgaya, where the Buddha attained enlightenment,” His Holiness told the audience, “but being here is not about saying prayers or engaging in ritual activities. The Buddhas don’t wash unwholesome deeds away with water, nor do they remove the sufferings of beings with their hands, nor do they transplant their own realization into others. It is through teaching the truth of suchness that they help beings find freedom. This is a unique feature of the Buddha’s doctrine and it means we have to pay attention to what he taught.

“Other religious traditions teach about a creator, which makes for philosophical complications, but their message of love and compassion is good. Teaching from his own experience, the Buddha advised us to accumulate skilful means and wisdom.

“The teachings recorded in the Pali Tradition represent the fundamental basis of the Buddha’s teachings. In the first turning of the wheel of Dharma he explained the Four Noble Truths. The second turning of the wheel, his exposition of the Perfection of Wisdom teachings, was not recorded by ordinary beings but by Bodhisattvas like Manjushri, Vajrapani and Samantabhadra.

“The first causal pair of the Four Noble Truths dealt with suffering and birth in cyclic existence and its cause. To answer whether that can be overcome, he taught the truth of cessation and the path to it. In elaborating on the Four Noble Truths, the Buddha explained their 16 characteristics. The truth of suffering, for example, can be understood as being impermanent, in the nature of suffering, empty and selfless. The characteristics of the truth of the cause of suffering are causes, origin, strong production and conditions.

“The ultimate cause of suffering is ignorance. When its antidote, wisdom, is applied, mental afflictions are overcome and cessation, characterized as definite release, is achieved. This is what the path entails. It is also important to recognise the nature of the mind and that destructive emotions are not part of it. Suffering is rooted in an ignorance of reality—as such it has no sound basis and can be overcome. When you understand the true nature of the mind, that it is clarity and awareness, you can see that the mental afflictions are temporary.

“Having mentioned emptiness in the first turning of the wheel, the Buddha elaborated on it during the second turning when he explained the perfection of wisdom. Then, for those who could not comprehend that, he gave a third turning of the wheel, as recorded in the ‘Unravelling of Thought Sutra’. At the same time he revealed the clarity and awareness of the mind, the subjective clear light, while the perfection of wisdom deals with the objective clear light. The mind of subjective clear light is the basis for the practice of tantra.

“The Buddha Shakyamuni taught according to his own experience from when he was an ordinary being through his training on the path to becoming a bodhisattva. We too can transform our unruly minds to attain the state of a Buddha.”

His Holiness asked whether the material and technological development we see today guarantees a happy world. He suggested that even in highly developed countries people are miserable because they do not know how to control or discipline their minds. We have anger and hatred within us and religions teach about what counters them—compassion and loving kindness—but their followers don’t pay sufficient attention. Indian traditions also counsel ahimsa or non-violence.

Theistic traditions’ explanations of a creator God whose nature is infinite love allow their followers to see themselves and their fellow beings as children of such a God. Followers of non-theistic traditions relying on explanations of the law of causality, like some of the Samkhyas, the Jains and Buddhists, understand that when you do good to others it brings about happiness and when you do harm it gives rise to suffering. Whether we follow a religion or not, as human beings we all need compassion. Our mothers give us our start in life and our first experience of love and affection.

Love is defined as a wish that others be happy; compassion is the wish that they be free from suffering. If you cultivate love and compassion within yourself, His Holiness advised, it will ensure happiness, good health and peace of mind.

“The teaching today will be ‘The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas’, which will serve as a preliminary to the Vajrabhairava empowerment and the cycle of teachings concerning Manjushri. The commitment for the Vajrabhairava empowerment is to cultivate the awakening mind of bodhichitta and the view of emptiness daily. That for the Manjushri cycle is to say one ‘mala’ round of ‘Mig-tse-mas’.

“The foundation of Buddhism is monastic discipline. Tibetans follow the Mulasarvastivadin tradition, as outlined in the ‘Pratimoksha Sutra’, the ‘Sutra of Individual Liberation’ recorded in Sanskrit. Monastics in Thailand and elsewhere in Southeast Asia follow the Theravada Tradition, whose ‘Patimokkha Sutta’ is preserved in Pali. Differences in the rules they delineate are relatively minor.

“Although on occasion the Buddha referred to a self that was like the carrier of a load in relation to the psycho-physical aggregates, the mind-body combination, in the second turning of the wheel he made clear that nothing whatever has any independent existence. The Nalanda Tradition encourages analysis of the Buddha’s word, coming to grips with them through reason.

“In Tibet, in the 7th century, King Songtsen Gampo had close relations with China. He married a Chinese princess who brought an important statue of the Buddha to Tibet. Nevertheless, when he wanted to refine Tibet’s alphabet and writing he modelled them on the Indian Devanagari script. Similarly, in the following century, when Trisong Detsen wanted to know more about Buddhism, he invited the Nalanda master Shantarakshita from India to Tibet. He set about establishing the Buddha’s teachings but ran into obstacles. He recommended Guru Padmasambhava be invited to deal with them. Thus, Tibetans became the custodians of the Nalanda Tradition.”

His Holiness explained that the text he was going to read, ‘The Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas’ he received from Khunu Lama Rinpoché, Tenzin Gyaltsen. He compared the line in the verse of homage that refers to seeing all phenomena as lacking coming and going to verses at the beginning of Nagarjuna’s ‘Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way’.

The reference in the first verse to the rarity of finding a fully qualified human life prompted His Holiness to state that there are two goals: higher rebirth and liberation. He cited sixteen causes of higher rebirth listed in Nagarjuna’s ‘Precious Garland’. They consist of thirteen activities to be avoided, the ten unwholesome deeds: killing, stealing and adultery; false, divisive, harsh, and senseless speech; covetousness, harmful intent, and wrong views. Three additional activities to be restrained include drinking alcohol, wrong livelihood and doing harm. There are three further activities to be adopted—respectful giving, honouring the honourable, and love.

Aryadeva also advises:

First prevent the demeritorious,

Next prevent [conceptions of] self;

Later prevent views of all kinds.

Whoever knows of this is wise.

Realization of emptiness overcomes not only mental afflictions, but cognitive obscurations too. The consequence is liberation.

His Holiness drew attention to the earlier and later disseminations of the Buddha’s teachings in Tibet. During the first, in the 8th century, Shantarakshita taught and encouraged the translation of Buddhist literature. His student Kamalashila came to Tibet and composed the three volume ‘Stages of Meditation’. After Lang Darma, the teaching declined. For 60 years monks were barely seen in Central Tibet, although their ordination lineage was later restored. In 11th century, as part of the later dissemination, Atisha came to Tibet and composed the ‘Lamp for the Path’ that presented progress on the path in terms of the three kinds of person.

The first verse concerning the thirty-seven practices highlights the special qualities of life as an intelligent human being that enable critical thinking. The reason for giving up your homeland, as mentioned in the second verse, is explained in the third in terms of cultivating solitude to be able to reflect and meditate. First becoming aware of the Two Truths—conventional and ultimate—then the Four Noble Truths yields understanding of what the Buddha taught, his role and that of the Sangha.

The fourth verse mentions impermanence in terms of consciousness, the guest, leaving the body. Consciousness is what goes on from life to life. His Holiness pointed out that scientists are beginning to acknowledge that consciousness is not simply dependent on the brain, but has an impact on it. He observed that as the particles of our physical beings can be traced back to particles at the time of the Big Bang, consciousness, preceded by a continuum of similar type—consciousness—continues from past to future lives.

The fifth verse recommends the shunning of bad friends, while the sixth advises cherishing the spiritual teacher. His Holiness spoke of scrutinising a teacher’s qualities and reflecting on the advantages of relying on such a person, as well as the shortcomings of not doing so. Once you have received his, or her, instruction, put it into practice. His Holiness remarked that the sixth verse completed the teaching related to a person of low capacity and announced that he would stop there for the day. He will resume his explanation tomorrow.