Teachings at Shewatsel

July 30, 2018

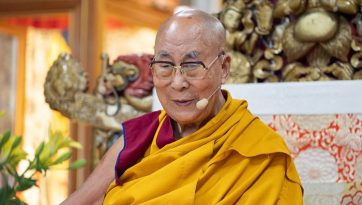

Leh, Ladakh, J&K, India – The sun was already bright and warm when His Holiness the Dalai Lama left his residence at the Shewatsel Phodrang to walk to the teaching pavilion on the adjacent teaching ground. Thiksey Rinpoche and LBA President Tsewang Thinles walked with him. All along the way members of the public pressed against the fence in hope of getting closer to His Holiness. Here and there he stopped to pat a child’s cheek or place his hand on the head of an older man or woman.

In his efforts to be as inclusive as possible His Holiness walked to the furthest corners of the front of the stage to wave to people nearby as well as those in distant parts of the crowd of an estimated 20,000. Meanwhile, nuns from the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies engaged in a dynamic debate in front of the stage. They were followed by students from Ladakh Public School.

After taking his seat on the throne, His Holiness remarked that he was tickled to see that the debating school students included an enthusiastic Sikh boy. He noted how important debate can be in sharpening understanding of the topic under study and thanked the schoolchildren for their contribution. Introductory prayers included the ‘Three Continuums’, which praises the qualities of the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, and the ‘Heart Sutra’.

“Last year we read up to the end of Chapter 6 of the ‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’,” His Holiness explained, “so we’ll go on from there. Shantideva is reported to have composed this text in the 8th century. It draws on the teachings of the extensive path lineage which Maitreya passed to Asanga and the profound view lineage that comes from Nagarjuna, sometimes referred to as the second Buddha. This teaching can be referred to as representing the great conduct lineage.

“Maitreya’s ‘Ornament for Clear Realization’ explains the implicit content of the perfection of wisdom teachings; Nagarjuna clarifies the explicit content, which is the theory of emptiness. Maitreya’s ‘Sublime Continuum’ explains Buddha nature, while his five treatises as a whole outline the bodhisattva path.”

Alluding to the various schools of Buddhist philosophy, His Holiness observed that the Vaibhashikas (Particularists) and Sautrantikas (Sutra Followers) teach the selflessness of persons, whereas the Chittamatrins (Mind Only School) and Madhyamakas (Middle Way School) teach the selflessness of phenomena as well. While asserting the true existence of consciousness, Chittamatrins deny the external existence of things, which they say are the result of imprints on our minds. His Holiness added that there are quantum physicists who suggest that the conviction that nothing exists objectively tempers emotional response such as attachment.

The Madhyamaka School is primarily divided into the Svatantrika (Autonomist) and the Prasangika (Consequentialist) Schools, although there is a branch of the former which incorporates Yogachara (Practitioners of Yogic Conduct) ideas. Where the Svatantrikas allow some kind of objective existence, the Prasangikas refute any objective or independent existence of things or experiences.

Turning back to the ‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’, His Holiness told the crowd, “I received transmission and explanation of this work from Khunu Lama Rinpoche, Tenzin Gyaltsen. He was a dedicated practitioner of what it has to say. At one time, as he cultivated practice of the awakening mind of bodhichitta, he would compose an appreciative verse every day. These verses were eventually compiled as the ‘Jewel Lamp’ and it was transmission of this that I sought first. I received the ‘Guide’ afterwards. Because he felt the practice of the awakening mind is so helpful, Khunu Lama Rinpoche asked me to teach it as much as I could.

“‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’ can be summarized into three parts—conduct by which you enter into the practice; the actual practice and accomplishment of the practice. It deals with the path leading to enlightenment rooted in the development of wisdom, on the basis of which you cultivate the conduct of a bodhisattva.”

His Holiness reviewed the titles and contents of the chapters of the book in relation to practice of the six perfections. He observed that there is no chapter dedicated to generosity, but the fact that the whole work deals with giving body, resources and virtues makes up for it.

“Of the ten chapters, the most important are Chapter 6 dealing with patience and Chapter 8 entitled meditation,” His Holiness continued. “If we are to cherish others more than ourselves, we need to overcome anger, and patience is the anti-dote to it. Chapter 8 shows that cherishing self alone leads to our ruin. What it primarily teaches is the practice of equalizing and exchanging self with others.”

After reading the first lines of Chapter 7, ‘Having patience I should develop enthusiasm, for awakening will dwell only in those who exert themselves,’ His Holiness mentioned that progress on the path doesn’t depend only on bodhichitta, wisdom is necessary too. The moment you have a genuine experience of bodhichitta, you enter the bodhisattva path, but you still need to train further. After the path of accumulation, the path of preparation involves the combination of a calmly abiding mind and insight focussing on emptiness. You progress to the path of seeing, where you realize emptiness directly and eliminate mental afflictions.

After developing the path of seeing and achieving cessation, you enter into the path of meditation and progress from the second bodhisattva ground to the tenth. Finally, you develop the path of no more learning that is the antidote to the residual stains left by mental afflictions. When all these defilements, including the imprints of negative emotions are cleared, you attain Buddhahood. This five tiered path is reflected in the mantra from the ‘Heart Sutra’.

When the Buddha says, “Tadyata gateh gateh paragateh parasamgateh bodhi svaha” (“It is thus: Proceed, proceed, proceed beyond, thoroughly proceed beyond, be founded in enlightenment”), he is telling his followers to proceed through the five paths:

gateh—the path of accumulation;

gateh—the path of preparation;

paragateh—the path of seeing;

parasamgateh—the path of meditation;

bodhi svaha—the path of no more learning.

“To follow the path requires enthusiasm and effort, but you need to understand the advantages of these qualities. Their opponents are, for example, laziness and low self-esteem. Until you understand that laziness is an obstacle, you won’t be motivated to overcome it.

“Reflecting on impermanence is helpful, as the early verses of Chapter 7 indicate. We are healthy and happy here now, but whether we will all meet again tomorrow isn’t guaranteed. Should death come, fame and wealth, friends and family will be of no help. Our only support will be the positive imprints of the virtuous actions we’ve done.

“Today, there are 7 billion human beings in the world and most of them think only of material gain. Very few think about the inner world of the mind. Many of us who look to the Buddha for inspiration neglect to consider that whether we make progress in the path depends on whether we make the effort. We also tend to think of our opponents as outside us, whereas the real enemy is within. The second kind of laziness is attraction to wrong-doing, while the third is low self-esteem, defeatism, thinking, ‘I can’t really do it’. Coming to understand the equality of self and others generates enthusiasm for the path.

“So, having mounted the horse of the awakening mind

That dispels all discouragement and weariness,

Who, when they know of this mind that proceeds from joy to joy,

Would ever lapse into despondency?”

As he read on, His Holiness pointed out that verses 43 & 44 indicate the results of virtue and wrong-doing. He explained that the mention of Vajradhvaja relates to a chapter in the ‘Array of Stalks’ or Avatamsaka Sutra. Shantideva’s advice to dispel despondency is to recall the advice in the chapter on conscientiousness and then joyfully rise to the task.

Having completed his reading of Chapter 7, His Holiness went straight on to Chapter 8, which begins by discussing how to develop concentration and how to surmount what obstructs it. He read briskly up to verse 89 & 90 which is where instruction on developing the awakening mind of bodhichitta and meditating on the equality between self and others begins.

I should protect all beings as I do myself

Because we are all equal in (wanting) pleasure and (not wanting) pain.

The discussion of the advantages of developing and putting compassion into practice and the disadvantages of not doing so culminate at verse 104 with the question—-‘But since this compassion will bring me much misery, why should I exert myself to develop it?’—The retort is, ‘Should you contemplate the suffering of living creatures, how could the misery of compassion be more?’

Highlighting the advice that if you’re selfish, you’ll never be happy, His Holiness noted the powerful impact of verse 130.

If I do not actually exchange my happiness

For the, sufferings of others,

I shall not attain the state of Buddhahood

And even in cyclic existence shall have no joy.

Verse 140 begins an exercise in exchanging self and others involving reflection on envy, competitiveness and self importance. You are jealous of someone higher than you thinking—he’s honoured, but I am not. You are competitive and wish to excel someone who is your equal and look forward to humiliating someone inferior to you. From verse 155 the faults of self-cherishing are explained.

“The practice of exchanging self and others brings home to us the disadvantages of cherishing yourself instead of others. If you cherish others more than yourself in this life and the next, great benefits will accrue.”

His Holiness looked at his watch and announced, “It’s time for lunch. See you tomorrow.” Waving to the crowd as he left, he drove back to the Phodrang.