Teaching Young Tibetans

June 3, 2019

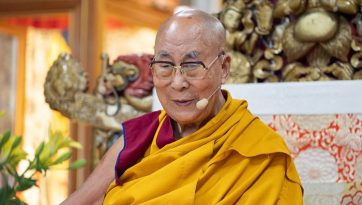

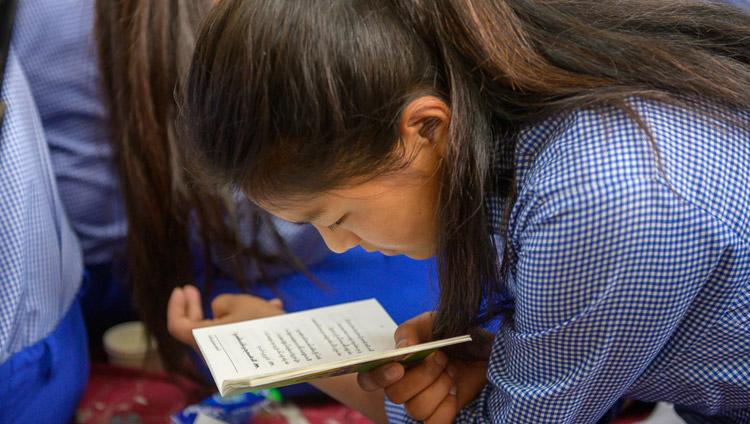

Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – The weather was warm and humid as His Holiness the Dalai Lama walked to the Tsuglagkhang, the Main Tibetan Temple, from his residence this morning. An estimated 8000 members of the public, 400 Tibetan Children’s Village (TCV) students from classes 9,10,11 & 12 and 800 Tibetan college students filled the temple, the spaces around it and the yard below.

Referring to a custom he began in 2007, His Holiness told the audience that his main aim today was to teach young Tibetans and the text he was going to go through was Thokmey Sangpo’s ‘37 Practices of Bodhisattvas’.

“The students among you may have been born in India, but you are Tibetan by ancestry. Those of us who are Tibetan will remain so until we die. There are myths about the Tibetan people’s origins to which I don’t pay much attention. However, there is archaeological evidence that people have been living in Tibet for 30-40,000 years. Nevertheless, what is special about us is our religion and culture. In 7th century, King Songtsen Gampo gave instructions for the creation of a script in which to write Tibetan. It was based on the Indian alphabet with vowels and consonants. So, although Tibetan spoken language is different from both Chinese and Indian languages, the model for our writing was Indian.

“In 8th century Shantarakshita was invited to Tibet by King Trisong Detsen. He advised that since we had our own language and writing we should study Buddhism in Tibetan rather than relying on Sanskrit. It’s said that despite his advancing age, Shantarakshita himself learned some Tibetan. He recommended that we translate as much Indian Buddhist literature into Tibetan as we could. The result is that our Kangyur collection, containing translations of the words of the Buddha, consists of about 100 volumes, while the Tengyur collection that includes subsequent Indian treatises consists of 220 volumes. Each text begins a gesture of authenticity, ‘the title of this work in the Indian language is such and such; the title in Tibetan is …’

“Buddhism arose like the sun over Asia bringing illumination to many. In the west, Christianity prevailed, in the Middle East, Islam, whereas in India various Hindu schools, Jainism and Buddhism flourished. What further distinguishes India is that followers of all the world’s major religious live here side by side. An example of the atmosphere is the Parsee community, Zoroastrians originally from Persia, who, though few in number, live amidst millions of Hindus and Moslems in Mumbai quite without fear. Indian religious traditions show each other respect.”

His Holiness mentioned Taxila, an ancient Indian centre of learning that preceded Nalanda University. Nalanda produced many great masters, whose calibre we can judge by what they wrote. Their works, originally composed in Sanskrit, are available to us today in Tibetan translation. His Holiness remarked that in the countries of South-east Asia Buddhist literature is preserved in Pali. He explained that he refers to the Sanskrit and Pali traditions rather than the more disparaging Lesser and Greater Vehicles (Hinayana and Mahayana).

His Holiness observed that the Buddha’s first round of teachings, including the Four Noble Truths, a rough account of selflessness, single-pointed concentration and so forth, was first preserved in Pali. The second round dealing with the Perfection of Wisdom teachings was given to a select, powerfully intelligent group on Vulture’s Peak. He noted that the extensive edition of the Perfection of Wisdom runs to 12 volumes, the intermediate edition to three and the short edition to one, with several shorter texts besides.

The ‘Heart Sutra’ explains emptiness of inherent existence when it states that ‘form is empty, emptiness is form’. This doesn’t imply nothingness, rather that form, or a material object, can be seen, but when its identity is sought it can’t be found. Things do not exist the way they appear. Quantum physics similarly says that nothing exists objectively. Because form arises in dependence on many factors, it has no inherent existence.

His Holiness also referred to the third round of the Buddha’s teachings in Vaishali and elsewhere when he taught the ‘Unravelling of Thought Sutra’. Having taught about the objective clear light in the Perfection of Wisdom series, in this third round he clarified the subjective clear light—the subtlest consciousness.

“When you meditate, you use the sixth mind, mental consciousness, not sensory awareness. In the west, mental consciousness is not much discussed. The function of the brain tends to be explained in relation to sensory perceptions. The mind can’t be explained solely on the basis of the brain. However, ancient India had a good understanding of the workings of the mind and emotions. There was knowledge of the subtle mind and its luminous quality, as well as recognition that destructive emotions arise in a coarse state of mind.

“The masters of Nalanda focused on the perfection of wisdom, exploring it in detail. Nagarjuna, for example, gave explanations not only in relation to scripture, but also in terms of logic and reason. The Buddha himself advised his followers not to accept what he taught at face value, but to examine it, much as a goldsmith tests gold, and accept it only after rigorous investigation has shown it to be logical and of benefit.

“In the Tibetan tradition we study by memorizing the ‘root text’, going through explanations of it word by word and debating with each other what we have understood. Dignaga’s and Dharmakirti’s extensive writings on logic and epistemology were translated into Tibetan. Later, Tibetan scholars like Chapa Chökyi Sengé (1109-69), the Abbot of Sangphu, and Sakya Pandita elaborated on these themes. Logic and reason are really helpful, a unique characteristic that I wanted to make you young Tibetans aware of. It’s something of which we can be proud.”

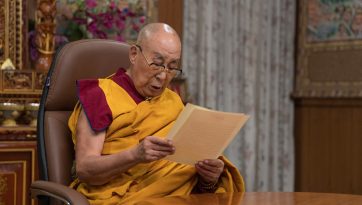

His Holiness began to read ‘The 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas’, noting that it opens with words of homage to Lokeshvara, the embodiment of compassion, and then in the third and fourth lines suggests that things do not exist as they appear. He glossed the Tibetan word for Buddha, revealing that it implies having eliminated all short-comings and having seen everything as it is. Jé Tsongkhapa refers to ‘not being captivated by either extreme view’.

Mental afflictions have no sound basis, they arise on the back of exaggeration. The opposite of anger, compassion and patience, are supported by reason.

The verses advise, give up your homeland, cultivate seclusion, give up bad friends and your good qualities will grow. Take refuge in the Three Jewels—the principal refuge is the Dharma, the experience of true cessation and the path to it. The Buddha is our teacher and the Sangha our companions in putting what he teaches into practice. The Buddhas do not wash unwholesome deeds away with water, nor do they remove the sufferings of beings with their hands, neither do they transplant their own realization into others. It is by teaching the truth of suchness that they liberate (beings).

Verse 8 counsels ‘never do wrong’, much as Aryadeva states in his 400 Verses:

First prevent the unwholesome,

Next prevent [ideas of a coarse] self;

Later, prevent [distorted] views of all kinds.

Whoever knows of this is wise.

Liberation is freedom from afflictive emotions.

Next, think about all sentient beings and develop the altruistic intention to attain enlightenment for their benefit—‘therefore, exchange your own happiness for the suffering of others’. This practice is elaborated on by Nagarjuna in his ‘Precious Garland’ and Shantideva in his ‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’. It is reiterated a few verses down, ‘without discouragement take on the misdeeds and the pain of all living beings’.

Things do not exist in the way they appear—the text says: ‘when you encounter attractive objects, though they seem beautiful like a rainbow in summer, don’t regard them as real’. Quantum physics tells us that as long there is an observer there is an observed object. The Mind Only School says that things have no external reality, while the Middle Way School states, ‘nothing whatever has any objective existence’.

The text concludes: ‘Destroy disturbing emotions like attachment at once, as soon as they arise’, ‘In brief, whatever you are doing, ask yourself “What’s the state of my mind?”’ ‘Dedicate the virtue from making such effort to enlightenment—this is the practice of Bodhisattvas’.

In his own closing remarks His Holiness recommended that Buddhism should be introduced on the basis of the Two Truths, conventional and ultimate truth. The Four Noble Truths can more clearly explained on that foundation.

“As I mentioned earlier,” His Holiness added, “the Nalanda Tradition was illuminating like the sun. Those of us who live in freedom have the opportunity to keep alive this vast tradition of Buddhism—do your best.”

As he walked slowly along the temple corridor and down the steps into the yard, His Holiness stopped frequently to greet the many individuals young and old waiting, their hands folded in respect, smiles on their faces, to catch his eye. Then he drove in a car the short distance back to his residence.