Observing the Day of Miracles

February 19, 2019

Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – The skies were clearing this morning after continuous overnight rain had left the ground wet underfoot and deposited fresh snow on the mountains and hills behind Dharamsala.

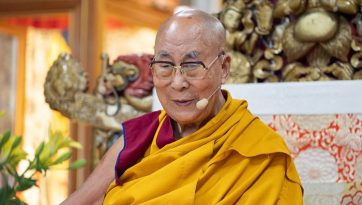

A sharp fresh breeze blew as His Holiness the Dalai Lama was escorted by yellow hatted monks playing horns, swinging censers and bearing a ceremonial yellow umbrella from his residence to the Tsuglagkhang. The yard and areas around the temple were packed with people and His Holiness returned their greetings as he walked through. Seated inside the temple were monks as well as retired and serving members of the Central Tibetan Administration.

His Holiness took his seat on the throne and the burly chantmaster declaimed the Heart Sutra and the long prayer to the Lam Rim lineage lamas, including the Kadampa masters, in deeply resonant tones.

“We’re gathered on this special day on which we celebrate the Buddha’s having performed miracles at Shravasti in response to a challenge from six rival spiritual teachers,” His Holiness explained. “In Tibet Je Tsongkhapa established this celebration as part of the Great Prayer Festival or Mönlam Chenmo. After some time it lapsed, but was revived once more during the time of Gendun Gyatso, the 2nd Dalai Lama.

“We weren’t able to celebrate these occasions during our first couple of years in exile, but re-established the custom as soon as we could after that. I decided to hold today’s teaching in the temple rather than down in the yard because it’s so cold today and because we’ll be meeting here to listen to the ‘Essence of the Middle Way’ over the coming days.”

Reading the Jataka Tales, accounts of the Buddha’s former lives, is part of the Great Prayer Festival. Yesterday, the reading had reached the story of Maitribala. Today, His Holiness began to read the story of Vishvantara, Prince of the Sibis, the life that preceded his birth as a Prince of the Shakyas. An accomplished exponent of generosity, the Prince is described as follows: “Though a youth, he possessed the lovely placidity of mind proper to old age; though he was full of ardour, his natural disposition was inclined to forbearance; though learned, he was free from conceit of knowledge; though mighty and illustrious, he was void of pride.”

His Holiness remarked that although the Buddha lived and taught more than 2500 years ago, there is still interest in his teachings. As do all other religious traditions, Buddhism encourages the practices of love and compassion, patience and tolerance. Different traditions propound different philosophical points of view to support such practice. Theistic traditions speak of a creator God embodying infinite love, qualities the faithful are inspired to emulate.

Non-theistic traditions observe the law of causality that to give help brings happiness and doing harm brings trouble. As social animals dependent on the communities in which they live human beings need to cultivate compassion. Followers of religion, His Holiness observed, should respect each other’s traditions while maintaining faith in their own.

“Buddhist teaching, like other traditions, commends us to take care of others, but what is different is that it expounds selflessness—that there is no independent self. Traditions that speak of an atman, a self independent of the aggregates or body/mind combination, explain that that is what goes from life to life. Buddhism rejects this and states that what goes from one life to the next is the subtle mind.

“In his first round of teachings the Buddha taught the Four Noble Truths. In the second round, as part of the Perfection of Wisdom, he explained that things are empty of intrinsic existence because they are dependently arisen. The self has no intrinsic existence because it is merely designated on the basis of the aggregates.

“During the third round, because there were people who could not yet accept the import of the perfection of wisdom and were at risk of falling into nihilistic views, the Buddha taught the sutra known as the ‘Unravelling of the Thought’. He also explained Buddha nature. Whereas in the second round of teachings he had referred to the objective clear light, during the third round he mentioned the subjective clear light that is also the basis of tantric practice.”

His Holiness quoted a verse that expresses the Buddha’s thought after enlightenment. ‘Profound and peaceful, free from complexity, uncompounded luminosity—I have found a nectar-like Dharma. Yet if I were to teach it, no-one would understand what I said, so I shall remain silent here in the forest.’ He clarified that ‘profound and peaceful’ refers to the first round of the Buddha’s teachings; ‘free from complexity’ refers to content of the second round, while ‘uncompounded luminosity’ refers to the third round.

The Buddha rejected the idea of an atman, a single, autonomous, permanent self. Nagarjuna elucidated this in his ‘Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way’, as can be seen in the first chapter. Chapter 26 explains the 12 links of dependent arising, beginning with ignorance. How things lack intrinsic existence is revealed in chapter 18 and chapter 24 shows that this is because they are all dependently arisen.

That which is dependently arisen

Is explained to be emptiness.

That, being a dependent designation,

Is itself the middle way.

There does not exist anything

That is not dependently arisen.

Therefore, there does not exist anything

That is not empty.

Through the elimination of karma and mental afflictions there is nirvana.

Karma and mental afflictions come from conceptual thoughts.

These come from mental fabrication.

Fabrication ceases through emptiness.

His Holiness pointed out that understanding things to be empty of intrinsic existence loosens our anger and attachment towards them. He reported that Indian nuclear physicist Raja Ramana had told him that the quantum physics notion that nothing has any objective existence seems to be new, but was anticipated long ago by Buddhist and other Indian thinkers. He added that American psychiatrist Aaron Beck’s observation that the negative light in which we hold someone or something with which we are angry is 90% mental projection—this also complies with Nagarjuna’s thought.

“It’s not enough just to cultivate the awakening mind of bodhichitta,” His Holiness said, “you also need the wisdom that understands that things have no independent or intrinsic existence. In this connection, Je Tsongkhapa made the request, ‘May I overcome all doubts by employing the fourfold reasoning’. To overcome wrong views, we need to study books like Nagarjuna’s ‘Fundamental Wisdom’, Chandrakirti’s ‘Entering into the Middle Way’ and Bhavaviveka’s ‘Essence of the Middle Way’. Then analyse and compare what they have to say. This is why faith is not enough, we need to use reasoned analysis.

“In Tibet we acknowledged a group of Indian masters known as the Six Ornaments and Two Supremes, but since such masters as Chandrakirti and Shantideva were left out, I composed a Praise to the Seventeen Nalanda Masters to include them.”

Resuming the story of Prince Vishvantara, His Holiness told of his great generosity and how a neighbouring king decided to test and take advantage of it by asking him to give away his majestic white elephant. Ministers were sent to make the request. Prince Vishvantara suspected that this was the ‘miserable trick of some king’, but ‘his attachment to righteousness did not allow him to be frightened by the lie of political wisdom’. He dismounted from the elephant and agreed to give it away. His own father’s ministers, angered by the loss this represented to their kingdom, complained to the prince’s father the king, resulting in the prince’s banishment.

His Holiness mentioned that the Kadampa tradition consisted of three lineages. Of these the Scriptural Lineage focussed on six texts—the Jataka Tales and the Tibetan equivalent of the Dhammapada, the Udanavarga. Also included were Shantideva’s ‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’ and ‘Compendium of Training’, Asanga’s ‘Bodhisattva Grounds’ and Maitreya’s ‘Ornament of Sutras’. Of these, the first two, the Jataka Tales and the Udanavarga provided the basis for faith. He went on to cite Haribhadra’s description of two kinds of practitioner, those who start with faith and the more intelligent who start with reason.

As he took up the ‘Eight Verses for Training the Mind’ His Holiness remarked that bodhichitta is cultivated on the basis of reason. This short text contains instructions not only for cultivating bodhichitta, but also for developing a view of reality. His Holiness stated that he first received an explanation of it from Tagdrag Rinpoché and later from Kyabjé Trijang Rinpoché. As he read through the verses, he commented that when we give to the poor we should do so respectfully; we should treasure ill-natured trouble-makers and give the victory to others, regarding enemies as precious teachers. We should cultivate the practice of ‘giving and taking’ and regard all things as like illusions, asking ourselves whether things really exist the way they appear.

Turning to Je Tsongkhapa’s ‘In Praise of Dependent Arising’ His Holiness stressed that the root of all suffering is ignorance. In the course of reading through the verses, he recounted the story of Je Rinpoché’s having a vision of Manjushri who gave him instructions. When Je Rinpoché told him he had difficulty understanding them, Manjushri told him to study the classic texts and to engage in practices of purification and accumulation of merit. To do this he recommended he go into retreat.

Because Je Rinpoché was teaching a large group of students at the time, some friends told him that to break off and go into isolated retreat might attract criticism. When this was reported to him, Manjushri retorted, “I know what’s best for you to help other beings.” Consequently, with eight close disciples, Tsongkhapa entered a long retreat at Chadrel Hermitage in 1392. He had a dream of Nagarjuna and his disciples. One of them, who he identified as Buddhapalita, came forward and touched a book to his head. Next day, while reading ‘Buddhapalita’ Je Rinpoché gained a subtle insight into emptiness and dependent arising’s being simultaneous and concurrent. As a result he developed the special respect for the Buddha that is expressed in this text.

Next, His Holiness gave a reading of his Praise to the 17 Masters of Nalanda. He gave particular emphasis to the kindness of Shantarakshita and Kamalashila who were responsible for establishing the Nalanda Tradition with its combination of logic and philosophy in Tibet.

“In the past we Tibetans lived in isolation,” His Holiness observed, “but coming into exile has enabled us to share the Nalanda Tradition and its basis in reason with others. This is an inspiration to Tibetans in Tibet, who rejoice that our traditions will not die out. Meanwhile, we in exile take inspiration from those Tibetans’ unflinchingly determined spirit.

“Keeping our knowledge and traditions alive is a source of pride and those from the CTA who have contributed to this can feel they have made their lives meaningful. There will be a sunny day for Tibet and the time when it will come is not far off. There are no reports that the great masters who wrote the Thirteen Classic Texts that we study sat chanting in deep voices—they employed analysis and wrote about what they understood. Monks of the seats of learning in South India belong to this tradition and should keep it up.”

His Holiness concluded by reciting the following verses from Nagarjuna’s ‘Precious Garland’:

May I always be an object of enjoyment

For all sentient beings according to their wish

And without interference, as are the earth,

Water, fire, wind, herbs, and wild forests.

May sentient beings be as dear to me as my own life,

And may they be dearer to me than myself.

May their ill deeds bear fruit for me,

And all my virtues bear fruit for them.

As long as any sentient being

Anywhere has not been liberated,

May I remain [in the world] for the sake of that being

Though I have attained highest enlightenment.

From the temple His Holiness walked back to his residence smiling and waving to members of the crowd as he went, stopping here and there to have a word with an old friend.