Meeting with Mind & Life – Interdependence, Ethics and Social Networks – Day Two

Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – When he entered the room this morning, His Holiness the Dalai Lama greeted the members of the Mind & Life Institute, Mind & Life Europe and their friends with a broad smile and a wave.

As soon as he’d taken his seat, he announced that he wanted to say something about the mind.

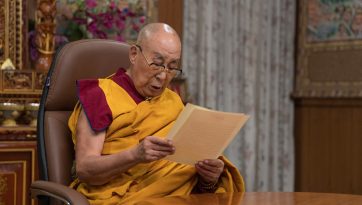

His Holiness the Dalai Lama speaking on the second day of the Mind & Life Conversation on Interdependence, Ethics and Social Networks at his residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on October 13, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

“Scientists haven’t investigated consciousness very deeply. They tend to think of the mind in relation to the brain, and yet the mind is something other than that. The mind is not a product of the brain. It is its own entity. Today’s mind is a continuation of yesterday’s mind. The mind is something worth finding out more about.

“When it comes to the start of a human life, the meeting of the physical factors doesn’t necessarily result in a conception. A third factor is consciousness. And for this reason, it would be worthwhile investigating what consciousness is.

“Trying to account for the origin of a person’s life only on the basis of their body would be difficult and unsatisfactory. We observe that twins, despite sharing a physical origin in the same womb, display differences in their personal characteristics.

“The nature of consciousness is said to be clarity and awareness and it is difficult to argue that this is a product of the brain.”

Richie Davidson interjected, “One of the things you’ve pointed out to us is that the scientific belief that the mind is the same as the brain is a belief not a fact. This is at the heart of what we have gleaned from you. Indeed, we scientists have not made real progress in investigating this over the last 100 years.”

“The brain is part of our body,” His Holiness continued. “And consciousness depends on the brain but is still separate from it. Consciousness and the body are two different things. We experience peace on a mental level and by comparison physical comfort is not that important. In the modern world we have neglected to explore how to find peace of mind.

“We have five sense organs that give rise to sensory consciousness, but we also have mental consciousness. Meditation, for example, is a function of mental consciousness—and it’s worth learning about.

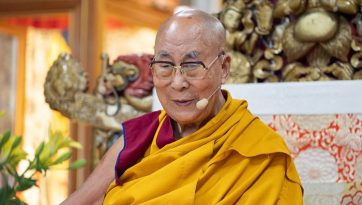

His Holiness the Dalai Lama gestures as he makes a point during his opening address on the second day of the Mind & Life Conversation on Interdependence, Ethics and Social Networks at his residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on October 13, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejo

“When we seek the source of consciousness, we find that it is a continuity. As I said before, today’s consciousness is a continuation of yesterday’s consciousness. Recognizing that continuity prompts questions about previous lives since there are young children who have clear memories of them.

“The idea that the mind, consciousness, is a continuity also contributes to a sense that we can cultivate the mind’s qualities. At the same time, the mind is not a monolithic thing. There are levels of consciousness of varying subtlety. Vajrayana literature describes these levels in detail as well as the way coarse levels of consciousness dissolve into subtler levels.

“One indication of subtler levels of mind can be seen in the case of people who are declared clinically dead and yet whose bodies remain fresh because the subtlest level of consciousness is yet to depart.

“Practitioners of meditation familiarize themselves with the dissolution of different states of consciousness at the time of death, which enables them to recognise without effort when the innate clear light, the subtlest level of consciousness, manifests.

“What we see here is a yogi, a practitioner, using a naturally occurring process. He or she seizes the opportunity of the natural process of dying and maintains an awareness of the different stages of dissolution as they take place, ultimately reaching the stage referred to as ‘all emptiness’ or clear light. The yogi uses that state of pure luminosity to focus on emptiness. In other words, he or she uses the subtlest state of mind to realize emptiness. Such a yogi, partly guided by karma, is said to be able to choose where he or she will next take birth.”

Amy Cohen Varela, Board Chair of Mind & Life Europe told His Holiness that today was a European day. She explained that Gábor Karsai, Managing Director, Mind & Life Europe had expected to be in Dharamsala, but at the last minute had tested positive for covid and had been unable to travel. She read a message from him in which he celebrated 35 years of sharing research results about contemplative practice. “It gives hope,” he said. “Cultivating the mind in the midst of suffering is a real antidote to the challenges we face.” He added a hope that a social network can be created that will benefit all beings.

Amy Cohen Varela, Board Chair of Mind & Life Europe introducing the days program on the second day of the Mind & Life Conversation on Interdependence, Ethics and Social Networks at His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on October 13, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

Today’s moderator, Martijn van Beek, recalled that yesterday Joe Henrich referred to how evolution and collaboration had made human beings dominant in the world. Molly Crocket, meanwhile, showed that more positive stories and gatherings can help us better recognise what we have in common. He introduced the day’s first presenter, Hanne De Jaegher, a philosopher and cognitive scientist who follows in the footsteps of His Holiness’s friend Francisco Varela. She studies participatory sense-making and what happens when people meet.

She told His Holiness, “I study how people interact with each other. We do interact despite differences between us. The question is how to create trust. I’ve watched you interact with your friend Bishop Tutu. I’ve observed how you tease each other and how you are able to recognise what you have in common and what is different between you. There is an important playfulness between you. I’ve wanted to ask you, do differences matter when we try to interact?”

His Holiness’s bald answer was, “No. Recognizing differences between us is something we create for ourselves, and to over-emphasize this leads to problems. If, on the other hand, we see each other primarily in terms of being human beings we can easily interact.”

“I agree,” De Jaegher replied, “this message is important. When I’m here I value the opportunity to learn about Tibetan culture. It’s an opportunity to recognize what’s different and what we have in common with each other.”

“There’s no use preserving narrow-minded attitudes,” His Holiness told her.

His Holiness spoke of how Shantarakshita taught Tibetans about the different schools of thought that flourished in eighth century India which enabled them to see things from different angles and to debate different points of view. De Jaegher noted that debate is a clear way to learn from each other.

Hanne De Jaegher, a philosopher and cognitive scientist, delivering her presentation on the second day of the Mind & Life Conversation on Interdependence, Ethics and Social Networks at His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on October 13, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

To illustrate the idea of interaction she described how you might find yourself walking down a corridor and you encounter someone else coming towards you. You step aside, and they step aside in the same way. This changes us. There is an interaction that shows us something about the sameness we share and our individual characteristics.

His Holiness observed that communication is a reflection of our having to avoid conflict and live together.

Martijn van Beek summed up Hanne De Jaegher’s presentation as showing the importance of meeting and interaction. Next, he introduced Abeba Birhane, whose work focuses on AI, artificial intelligence.

She told His Holiness what a pleasure it was to be here and that she wanted to talk about digital technology. She asked if he had a computer and seemed a little taken aback when he told her, “No.” She stated that almost everyone else in the room had a smart phone which serves as a conduit to digital technology.

She mentioned facial recognition which is used in the processing of visas, registration of refugees and so forth. On the one hand this kind of technology is regarded as efficient, but there are also drawbacks involved. One of these is that while facial recognition is almost 100% accurate in dealing with white faces, it is 35% inaccurate when it comes to recognizing people of colour. This is important because judgements are made about people on the basis of such technology’s findings and the companies operating such technologies are now market leaders.

“Generally speaking,” His Holiness responded, “whether or not technology can be thought of as good or bad depends on how it is used. We human beings should not be slaves to technology or machines. We should be in charge.”

“Companies value performance and efficiency,” Birhane told him. “But justice and fairness are not valued in the same way. How such technology is used makes all the difference. It seems that technology companies are primarily interested in making money, not in rendering benefit.”

The day’s moderator Martijn van Beek looking on as Abeba Birhane, whose work focuses on AI, artificial intelligence, delivers her presentation on the second day of the Mind & Life Conversation on Interdependence, Ethics and Social Networks at His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on October 13, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

“I agree,” His Holiness affirmed. “Human values are regarded as of secondary importance. This is what happens when we are too materialistic. We must remember that we are human beings and we need to apply human values, whatever we do. Principally we need to be motivated by warm-heartedness. Technology is supposed to serve human needs; therefore, it needs to be guided by human values.

“There seems to be a sense that the more a country employs the kind of technology you’ve been talking about, the more superior it is. And yet the way we are born and the way we die are exactly the same wherever we are.”

Birhane observed that digital technology seeks out superficial differences. She asked His Holiness what he might have to say to the people working in this field.

“Technology of all kinds should be of benefit to humanity, as well as contributing to the protection of ecology.”

Amy Cohen Varela brought the session to an end telling His Holiness that delegates from the Mind & Life Institute and Mind & Life Europe wanted to express their joy at being here with him.

“Our friendship hasn’t come about as a result of one or two meetings,” His Holiness replied. “We’ve been friends for a long time. We share a genuine friendship based on trust.

“I became a refugee here in India. I lost my country. But then I met people from so many other places and felt happy to be part of this world. I also want you to know that for the Tibetans in Tibet, friends of the Dalai Lama are friends of Tibet. In my homeland there is a deep appreciation of our good relations—and in the end we believe truth will prevail.”