Entering into the Middle Way (2022) – Second Day

Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – When His Holiness the Dalai Lama stepped into the yard this morning on his way to the temple, he paused to pay attention to a great array of objects that people had placed on several tables to be blessed. Then, walking on, he looked repeatedly to either side of the path to smile and wave to members of the public.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama waving to people gathered on the street below as makes his way around the Kalachakra Temple in Dharamsala, HP, India on September 16, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

As he walked round the Kalachakra Temple he stopped to lean on the railing, look down and wave to people gathered on the street below. Likewise, from behind the back of the Main Temple he laughed and waved to people waiting to catch a glimpse of him from the road up to McLeod Ganj. Inside the temple, before sitting down, he greeted and saluted the Thai monks who are sitting around the throne.

The ‘Heart Sutra’ was chanted first at a steady pace by Vietnamese monks and nuns who followed the rhythm of a wooden fish. Next, it was recited by a group from Indonesia.

Addressing the audience estimated to number 6100 from 57 countries, including the specific patrons of the teaching, 650 Buddhists from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam, His Holiness observed that this was the second day of the teachings.

“All of us are the same in not wanting to suffer, but wishing to be happy. On this planet,” he went on, “there have been several founding teachers of various religious traditions, but it was the Buddha’s observation that suffering is not without causes. These causes arise from our actions and mental afflictions. He advised that we know suffering, get rid of its origin, achieve cessation and cultivate the path.

“We need to understand the nature and extent of suffering. Something may appear to be pleasurable, but is actually of the nature of suffering. Suffering and dissatisfaction are not outside us, they’re something we experience within. However, we can achieve their cessation by cultivating the path that consists of the Three Higher Trainings—ethics, concentration and wisdom.

A group from Indonesia reciting the ‘Heart Sutra’ in Indonesian as the start of the second day of His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s teachings at the Main Tibetan Temple Dharamsala, HP, India on September 16, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

“The Buddha taught that suffering must be known, but that there is nothing to be known. Its origin must be overcome, but there is nothing to be overcome. And the same is true of cessation and the path. These Four Noble Truths are the basis of the Buddha’s teaching, key to which is that the ultimate cause of suffering is a distorted state of mind. One way to counter this is to take account of the Four Seals:

All conditioned phenomena are transient.

All polluted phenomena are unsatisfactory or in the nature of suffering.

All phenomena are empty and selfless.

Nirvana is true peace,

“The Buddha’s teaching is logical and based on cause and effect. Practising it is not a question of praying to the Buddha. It’s about overcoming ignorance and distorted views by following the true path. When you reach the path of preparation you achieve some cessation, and on the path of seeing, you actualize cessation.

“Overcoming ignorance involves understanding what suffering is and that its cause is karma and mental affliction. It entails understanding that things do not exist as they appear. Nothing exists that is not dependent. Things are merely designated. Achieving cessation requires strength of mind. When you understand that it is possible to achieve cessation, you’ll follow the path.”

At this point His Holiness recited a verse from Jé Tsongkhapa’s ‘In Praise of Dependent Arising’:

Becoming ordained in the way of the Buddha

by not being lax in study of his words,

and by yoga practice of great resolve,

this monk devotes himself to that great purveyor of truth.

And he applied what it says to his own experience, noting that he had taken novice and fully-ordained monk’s vows in his youth. Since that time, having become a renunciant, he studied the teaching of the Buddha. The essence of this is to cultivate the awakening mind of bodhichitta and an understanding of emptiness. He stated that like Tsongkhapa, ‘by yoga practice of great resolve, this monk devotes himself to that great purveyor of truth—the Buddha.’

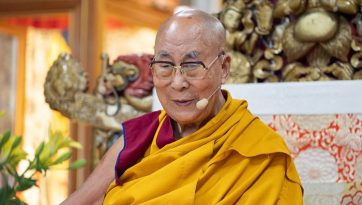

His Holiness the Dalai Lama addressing the congregation at the Main Tibetan Temple Dharamsala, HP, India on September 16, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

His Holiness announced that he’d be happy to answer questions from the audience. In doing so he explained that since grasping at the true existence of phenomena serves as the basis for grasping at the true existence of a person, it would be difficult to understand the selflessness of a person without realizing the lack of true existence of phenomena.

He added that other traditions and schools of thought assert a soul or self that is not dependent on the mental and physical aggregates, whereas the Buddha denied the existence of such a self.

His Holiness clarified that although developing single-pointed concentration is important, it is possible to understand through analysis that things have no essential existence. He recalled that the great Indian master Kamalashila, a student of Shantarakshita, was invited to Tibet by the then King, Trisong Detsen. He took part in the Samye Debate with Chinese teaches who advocated the importance of concentrated and non-conceptual meditation. The King decided that taking an analytical approach was more suitable for Tibetans.

His Holiness commented that by applying the sevenfold reasoning it would be possible to focus on the empty nature of an object, but that subsequently it would also be useful to analyse the mind that performed the analysis.

He told a woman who spoke of her dreams of people who have died that sometimes such dreams occur because of past connections and other circumstances. However, he counselled that dreams are not reliable.

His Holiness remarked that we all have a general sense of ‘I’, but that it’s when we think of that ‘I’ as not dependent on the aggregates and as their owner or controller that we grasp at the self of a person. There is a mere ‘I’ on the one hand and a grasping at an independent self on the other.

A member of the audience asking His Holiness the Dalai Lama a question on the second day of his teachings at the Main Tibetan Temple Dharamsala, HP, India on September 16, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

He recommended greater interaction between religious traditions that would lead to a clearer understanding of other ways of thinking and practice. He noted that the Buddha was not alone in adopting the homeless life, followers of other traditions do this too.

As far as spiritual practice is concerned, he suggested that thinking only of yourself doesn’t bring happiness. It gives rise instead to anxiety and suspicion. If, however, you concern yourself with the well-being of sentient beings extensive as space, you’ll find yourself calm and at ease. He quoted Shantideva’s advice:

For those who fail to exchange their own happiness for the suffering of others, Buddhahood is certainly impossible – how could there even be happiness in cyclic existence? 8/131

His Holiness conceded that saying prayers for your teacher’s long life can have some benefits, but far more effective is to practise the teaching he’s given, which, in the case of a Buddhist, involves bodhichitta and an understanding of emptiness. This gift of practice is what will really prolong the lama’s longevity.

His Holiness observed that a simple first step when coming to terms with suffering is to look at it from a wider perspective. On the one side think of yourself as just one among many human beings alive on this earth, on the other it can help to take other unforeseen circumstances into account. So long as we are steeped in self-cherishing attitudes we’ll encounter disturbances, but developing insight into selflessness can help us counter our negative emotions.

He reiterated that when we grasp at the self with attachment or anger, as something solid that seems to possess the aggregates, that is the object to be negated.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama answering a question from a member fo the audience on the second day of his teachings at the Main Tibetan Temple Dharamsala, HP, India on September 16, 2022. Photo by Tenzin Choejor

He recommended that a psycho-therapist might find it more effective to share her own experience than to prescribe practices borrowed from Buddhism for her patients. Asked to explain the easiest way to develop bodhichitta he mentioned both the seven-point cause and effect approach and the method of equalizing and exchanging self and others. The book that describes this latter method most vividly is Shantideva’s ‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’, from which he cited the following verses:

All those who suffer in the world do so because of their desire for their own happiness. All those happy in the world are so because of their desire for the happiness of others. 8/129

Why say more? Observe this distinction: between the fool who longs for his own advantage and the sage who acts for the advantage of others. 8/130

This same book encourages us to reappraise how we view someone who seeks to harm us. Although they appear to be hostile, with a wish to harm, it’s possible to see them as an object of compassion. Because this transforms our own attitude, we can view such an ‘enemy’ as a teacher.

Finally, a mother wanted to know how to bring her son up as a Buddhist. His Holiness told her, “Rather than trying to impose this or that set of ideas on your son, it would be better to offer him books to read, maybe even books I’ve written,” and he laughed, “so he can come to his own conclusions.”