Compassion in Action: a Conversation about Leadership

Thekchen Chöling, Dharamsala, HP, India – This morning His Holiness the Dalai Lama met with fourteen young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program and an accompanying group of invited guests. The Dalai Lama Fellows is a unique one-year leadership program for emerging social-change-makers that is designed to integrate contemplative work and intentional personal transformation with efforts to bring about positive change in their respective communities.

Chancellor of the University of Colarado, Philip P DiStephano, opening the meeting with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program along with accompanying guests at His Holiness’s residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on March 20, 2024. Photo by Ven Tenzin Jamphel

As soon as His Holiness had taken his seat in the meeting room the Chancellor of the University of Colorado, Philip P DiStephano, opened proceedings. He told His Holiness that he had come with friends and colleagues to share a conversation on compassionate leadership. He reminded His Holiness that the University of Colarado had hosted him in Boulder in 2016 and that they had engaged in a further virtual conversation in October 2021.

“It’s a joy to be with you and Dalai Lama Fellows from the University of Colorado, Stanford University and the University of Virginia,” he remarked. “This is an opportunity to shape tomorrow’s leaders.”

As part of her introduction, Moderator Sona Dimidjian told His Holiness that his advice had been a guide to her work in psychology and neuroscience and to her family.

“We seek your guidance again,” she told him, “for these young people who, looking out to the world see competition and conflict, war and suffering. And when they look inward, they see suffering, sorrow and despair.

Moderator Sona Dimidjian delivering her introduction during the meeting with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program along with accompanying guests at His Holiness’s residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on March 20, 2024. Photo by Ven Tenzin Jamphel

“Since the Dalai Lama Fellows program was launched in 2004 more than 200 Fellows from 50 countries have taken part. They wish to put your teachings into action, combining an inward and outward focus to bring about change in the world. Their hearts are open.”

Dimidjian reported that when she reached the gate to His Holiness’s residence this morning, she found the group of Dalai Lama Fellows singing together as they waited to enter. This served as a prompt for them to break into song once more as they chanted, “Open my heart, open my heart, let it overflow with love.” Dimidjian then asked His Holiness if he had a few words for them about how they could put compassion into action.

“First,” he replied, “I want to tell you how happy I am to be meeting with you here. Basically we have all been born of a mother and received maximum affection from her. It’s a natural response, we see other animals do this too. It’s an experience we all share in common, and it means we are all essentially the same. We survive because of our mother’s kindness. This is something very important to remember.

“While we’re still young, the sense of our mother’s affection remains vivid within us, but as we grow up and go to school, it begins to decline. How much better it would be if we could keep our appreciation of her kindness fresh and alive until we die? One way to do this is to make an effort to nurture a sense of compassion and warm-heartedness.

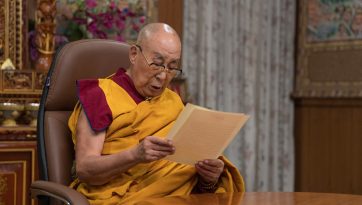

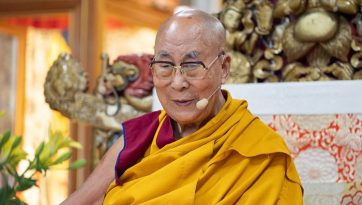

His Holiness the Dalai Lama speaking to young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program along with accompanying guests at his residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on March 20, 2024. Photo by Ven Zamling Norbu

“Wherever I go and whoever I meet, I smile and greet them warmly. That’s how everyone becomes my friend. The key thing is to be warm-hearted towards others. I believe warm-heartedness is part of our very nature. It brings about peace of mind and attracts friends. Our mother’s real gift to us is her smile and her affectionate warm-heartedness.”

Sona Dimidjian mentioned that she was excited to introduce seven Dalai Lama Fellows who, in pairs, would put questions to His Holiness. The Fellows were Khang Nguyen from Vietnam and Damilola Fasoranti from Nigeria/ Rwanda; Mansi Kotak from Kenya and Serene Singh from the United Kingdom; Brittanie Richardson from Kenya/ USA and Shrutika Silswal from India, as well as Anthony Demauro from USA. They asked him what they could do to promote a recognition of human values, shared and universal. They sought his advice about how to inspire others to choose service and the care of others as a way of life. They wanted to know how to employ compassion as a leader when feeling angry and frustrated and they enquired how to resist injustice while maintaining compassion even for oppressors.

Young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program asking His Holiness the Dalai Lama a question during their meeting at his residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on March 20, 2024. Photo by Ven Tenzin Jamphel

“If we were to keep the basic sense of affection that we received from our mother alive,” His Holiness replied, “there’d be no reason to quarrel with anyone. However, instead of thinking about what we have in common with other people, we tend to focus on the differences between us.

“Wherever I go, I think of myself as just another human being and I smile. I don’t think of myself as the Dalai Lama and somehow separate. And whenever I meet someone new, I feel they are just like me. We may have different names and our skin or hair may be a different colour, but these are just secondary differences.

“I just see other people I meet as human beings, as brothers and sisters. I don’t dwell on the differences between us, I think about the ways in which we’re the same. When I was very young, living in North-east Tibet, I played with the neighbouring children. I responded to them just as children like me. It was only later that I realized incidentally that many of them came from Muslim families and that my family was Buddhist.

“The essential thing we have to remember is that, when it comes down to it, we are all the same as human beings. Sometimes we forget our basic human values, our generosity and sense of kindness, because we let prejudice or negative discrimination take over. Whatever our religion, culture or ethnicity, at a fundamental level we are the same in being human. Thinking too much about being ‘Dalai Lama’ sets me apart from others, when I’m much more concerned with our common humanity.

A view of the hall during the meeting with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program along with accompanying guests at his residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on March 20, 2024. Photo by Ven Tenzin Jamphel

“As I’ve already said, young children are just open and friendly. They don’t discriminate between themselves and others. It’s only when they grow older that they become aware of ways in which we are different. And the risk is that this leads to conflict. The way to balance this out is to think about how we are all the same. This is what we must remind ourselves. At a fundamental level we have to acknowledge the oneness of humanity, that in being human we are just like each other. Our faces have two eyes, one nose and a mouth.

“The fact that people of different colour, nationality and so on can procreate and give birth to viable, fertile, healthy children confirms that as human beings we are fundamentally the same.

“We do have different, complementary identities, for example I’m Tibetan, I’m a monk and I have the name Dalai Lama, but the most important point is that I’m a human being.

“We are social beings, we make connections with each other, but that doesn’t seem to be enough to stop us allowing conflicts to develop. However, one of the benefits of internalizing a sense of the oneness of humanity, the conviction that as human beings we are all the same, is that it makes us more relaxed.”

Sona Dimidjian thanked His Holiness for welcoming the group and sharing his wisdom with them. She invited Vijay Khatri to make some closing remarks.

Vijay Khatri delivering his closing remarks during the meeting with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and young leaders taking part in the Dalai Lama Fellows program along with accompanying guests at His Holiness’s residence in Dharamsala, HP, India on March 20, 2024. Photo by Ven Zamling Norbu

“This week has been transformational,” he began. “As the saying goes, ‘The mind is not just a vessel to be filled, but a fire to be kindled.’ We have engaged with you and learned from you about compassion and warm-heartedness and we thank you for this kind gift.”

“As I mentioned earlier,” His Holiness responded, “when we’re very young we play with other children without any prejudice or suspicion between us. This kind of open, even-handed attitude is what we must preserve. We see each other in terms of ‘us’ and ‘them’ and this can lead to conflict. This is why it’s useful to regularly remind ourselves how much we have in common and that those we regard as ‘them’, not ‘us’, are human beings too.”

Sona Dimidjian wished His Holiness a peaceful, joyful day and told him the group looked forward to seeing him again tomorrow.