Three Principal Aspects of the Path

December 17, 2017

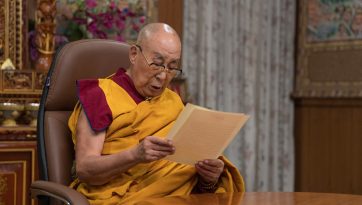

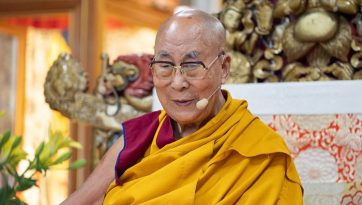

His Holiness took the stairs from his apartment down to the temple where he paid his respects before the enshrined images and greeted the distinguished Lamas before ascending the throne.

“Our original plans changed because I caught a cold,” His Holiness explained. “I was tired after the ordinations in Drepung, but today, after a day’s rest, I feel better.

“Ganden is the mother monastery of our tradition, founded by Je Tsongkhapa, which Gyalwa Gendun Drup described so well in his ‘Song of the Eastern Snow Mountain’.

Above the peaks of the eastern snow mountains

White clouds float high in the sky.

There comes to me a vision of my teachers.

Again and again am I reminded of their kindness,

Again and again am I moved by faith.

To the east of the drifting white clouds

Lies the illustrious Ganden Monastery, Hermitage of Joy.

There dwelled three precious ones difficult to describe

My spiritual father Lobsang Drakpa, and his two chief disciples.

Vast are your teachings on the profound Dharma,

On the yogas of the path’s two stages.

To fortunate practitioners in this Land of Snows,

Your kindness, O masters, transcends thought.

“Je Rinpoche was one of the greatest personalities to serve Buddhism in the Land of Snow. A Japanese scholar once told me he felt that reading what Je Rinpoche wrote you can tell the kind of person he was.

“Having come here to Ganden I decided to give this teaching so I won’t have visited without doing anything constructive.

“Je Rinpoche’s teacher Jetsun Rendawa inspired a generation to take special interest in the Middle Way View—including Je Rinpoche. Rendawa’s vast intelligence was compared to the unobstructed expanse of space. Now when we read Je Rinpoche’s writings based on his reading of numerous Indian commentaries we can trace the steady evolution of his view. Likewise, his works on Guhyasamaja illustrate the way his understanding of the illusory body clarified.”

His Holiness remarked that the tradition of studying the classic texts and great treatises was upheld by all Tibetan Buddhist Traditions, each of which also engaged in the application of epistemology and logic. He noted that while the Nalanda Tradition was influential in both China and Tibet, Dignaga’s and Dharmakirti’s major works on logic are all available in Tibetan, whereas only one small text of Dharmakirti’s was translated into Chinese.

Early Sakya scholars Kunga Nyingpo, Drogon Chögyal Phagpa and Sakya Pandita paid particular attention to the rules and function of logic. Rendawa was an heir to that tradition. He was among several superb scholars who deeply influenced Je Rinpoche. Another was Lhodrak Namkha Gyaltsen who gave him instructions in Dzogchen. His Holiness commended Tsongkhapa not only for being learned in many fields, but for applying what he learned in practice. This pattern of study and practice was maintained at the Three Seats of Learning around Lhasa—Ganden, Sera and Drepung—and Tashi Lhunpo.

“Here in exile we have kept up this tradition and now nuns too have taken up rigorous studies. The determination of the people of Tibet serves as a constant source of encouragement. The tradition we uphold is the pure tradition of Nalanda—I urge all of you to continue to keep it up.

“Tsakho Ngawang Drakpa wrote to Tsongkhapa from Eastern Tibet asking how to practise the Dharma. He received this ‘Three Principal Aspects of the Path’ in reply and the reassurance, ‘If you follow my words, I’ll guide in all your lives and when I manifest enlightenment, I’ll teach you first.’

“I must have received transmission and explanation of this text from Tagdrag Rinpoche, as well as from Ling Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche”

His Holiness explained that this text begins with an appreciation of the difficulty of finding human life and the importance of turning away attraction to this life. He remarked that this is different from the approach of the ‘Foundation of All Excellence’ that more closely follows the pattern of Atisha’s ‘Lamp for the Path’.

He digressed to mention that 3 or 4 years ago a Chinese scholar from Columbia University told him that he had explored Chinese historical documents. They reveal the existence of three empires—Tibetan, Mongolian and Chinese—as well as the fact that from the T’ang to the Qing dynasty—the Manchus who ruled at the time of the 13th Dalai Lama—there was no mention at all of Tibet being a part of China. What is also clear is that after Shantarakshita helped set up Samye Monastery, there were Chinese monks in the Department of Unwavering Concentration. In due course, Kamalashila, Shantarakshita’s disciple, came to debate with them.

By the 11th century King Jangchub Ö was so concerned by the decline of Buddhist traditions in Tibet that he requested Atisha to compose a text to restore them. The result was the ‘Lamp for the Path’. His Holiness explained that that text, and other subsequent Stages of the Path texts, begin with the need to rely on a Guru or spiritual mentor. His Holiness feels strongly that it’s more appropriate now to follow the approach of ‘Ornament for Clear Realization’, which starts by introducing the Two Truths, the Four Noble Truths and the qualities of the Three Jewels.

The Four Noble Truths were taught on the basis of causality. All Buddhist schools teach them. However, only when we understand the third noble truth—cessation—will we begin to understand what the Buddha’s teaching was about. Related to understanding the origin of suffering are the Twelve Links of Dependent Arising—and the first link is ignorance, which is to misconceive reality. It can be countered by understanding emptiness. As Aryadeva recommends in his ‘400 Verses’:

First prevent the demeritorious,

Next prevent [ideas of a coarse] self;

Later prevent views of all kinds.

Whoever knows of this is wise.

His Holiness’s close reading of the text elaborated on the determination to be free, the advantages of developing the awakening mind of bodhichitta, as well as the disadvantages of not doing so. He pointed out that unless you train the mind to aspire for Buddhahood, you won’t achieve it. In touching on the disadvantages of a self-cherishing attitude and the advantages of cultivating concern for others he quoted Shantideva:

Whatever joy there is in this world

All comes from desiring others to be happy,

And whatever suffering there is in this world

All comes from desiring myself to be happy.

The crux of the correct view is that things do not exist the way they appear. Despite appearances things are empty of any intrinsic existence whatsoever. His Holiness quoted a verse from one of the 7th Dalai Lama’s songs of experience:

Just as a cloud disperses in the autumn sky,

In the vision of my mind as being inseparably one with emptiness

All experiences and perceptions dissolve;

I, an unborn yogi of space.

Coming to the end of the text, His Holiness clarified that the paradoxical lines of the penultimate verse,

Appearances refute the extreme of existence,

Emptiness refutes the extreme of nonexistence;

represent the Consequentialist Middle Way (Prasangika-Madhyamaka) view, which also asserts that things exist merely by way of designation. He concluded with the comment that this short text presents the very essence of the Buddha’s teaching. He recommended that his listeners build on it by carefully scrutinizing particularly what Je Rinpoche has to say in his treatises on the Middle Way View.

“I thought I would like to teach for an hour and a half, and now it’s been two and a half hours. I often tell people that once I start I can talk and talk. I’d like to thank everyone who has made this occasion possible. I’d also like to thank you all for your prayers for my good health.”

His Holiness is due to leave Mundgod tomorrow for a two day journey by road to the Tibetan Settlement of Bylakuppe.