Teaching ‘Stages of Meditation’ and ‘Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas’ at Disket July 11, 2017

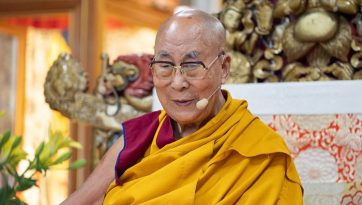

Disket, Nubra Valley, J&K, India – His Holiness the Dalai Lama is staying at the Disket Monastery Phodrang. This morning on his way to the teaching ground he stopped to perform a short consecration in the new assembly hall. Reaching the teaching ground he received and returned people’s greetings as he made his way to the throne. Before taking his seat he waved to the crowd to the left, right and straight ahead. A recitation of the Sutra Recollecting the Three Jewels was followed by the Heart Sutra and the Praise to the Seventeen Masters of Nalanda.

“Today, you’re going to listen to a Dharma discourse,” His Holiness began. “In Tibet and across the Himalayan region, people tend to think of Dharma in terms of reciting mantras or performing rituals. Gelukpas may think about the ‘Stages of the Path’. I’m 82 years old, I’ve seen a lot and I feel we’ve been too accustomed to focussing on teachings that were intended for specific groups or individuals rather than on the general structure of the. Here and now in the 21st century, when everyone’s so busy, I prefer to introduce people to Buddhism by summarizing the contents of our 300 volumes of classic Buddhist literature.

“The Four Noble Truths were given in an open public context, but the Perfection of Wisdom teachings were not. Consequently there are those who assert that the Mahayana is not the teaching of the Buddha, just as there are others who claim that tantra is not the Buddha’s teaching either. It’s because of such qualms that we need to pay more attention to the general structure of the teachings. Whether we follow the Nyingma and their Kama and Terma teachings or the Geluk and the Sergyu, Ensa and Shungpa lineages, our attention to specialist teachings becomes ground for differentiation.

“The Pali tradition teaches that the Buddha only turned the wheel of Dharma once. The Sanskrit tradition on the other hand speaks of three turnings of the wheel. The first turning dealt with philosophical views up to the Vaibhashika School and monastic discipline, the second dealt with the perfection of wisdom, including the Madhyamaka view and the third was the source for the Mind Only School. Another way of looking at this is to see the Two Truths as the basis, method and wisdom as the path and the two bodies of the Buddha as the result. This accords with the logical approach of the Madhyamakas. When you understand this you’ll be able to fend off challenges about the teachings of the Buddha.

“Starting with the Two Truths and going on to the Four Noble Truths, a disciple can come to understand true cessation and the true path and that that can be achieved because we have Buddha nature.”

His Holiness remarked that it is because the Buddha’s teachings can be presented in terms of logic and reasoning that aspects of them dealing with the mind and so forth are of interest to scientists. Logic and reason also have a role in relation to the three objects of knowledge—phenomena that are manifest and obvious; others that are slightly hidden and yet others that are very hidden. To understand extremely hidden phenomena it’s necessary to rely on textual authority or an experienced person.

His Holiness clarified that teachings about topics like emptiness can be verified by experience and declared that he has chosen to reject the existence of Mount Meru explicitly because neither he nor anyone else has any experience of it. He suggested that if it existed we should be able to see it as we travel around the world—and we do not. He added that the reason the Buddha appeared in the world was to teach the Four Noble Truths, not the measurements of the world or other aspects of cosmology.

“Generally speaking, the Dharma is something we need. There is a tendency to think that wealth, property, name and fame are sufficient. If they provided us with peace of mind and mental development, that would be good, but in the face of natural disasters like flooding, drought and earthquakes they are not of much help. Many of the other problems we face are of our own making. We can change them and how they affect us by transforming our minds.

“There may be sentient beings in other parts of the universe, but we can’t do much to help them. There is not even very much we can do to help the birds, animals and insects we see in this world. Those we can help belong to the 7 billion human beings alive today. They all want happiness rather than suffering and we can help them understand the value of peace of mind. There is value in understanding the advantages of love and compassion and the shortcomings of anger and fear.”

Reiterating that all major religions have the potential to promote and enhance the practice of love and compassion, harmony and respect among them is not only important but is feasible.

“We are gathered here to listen to teachings that began with the Buddha. After his enlightenment he is said to have thought—

“Profound and peaceful, free from complexity, uncompounded luminosity-

I have found a nectar-like Dharma.

Yet if I were to teach it, no-one would understand,

So I shall remain silent here in the forest.

“Eventually he turned the wheel of Dharma by teaching the Four Noble Truths. In that first turning of the wheel he referred to selflessness. In the second turning, he elaborated on that, explaining that not only is the person empty of inherent existence, so are the psycho-physical aggregates. In the third turning, he went on to teach the emptiness of Buddha nature. I find it useful to personalize the fourfold reasoning we find in the Heart Sutra by reflecting, ‘I am empty, emptiness is me; Emptiness is not other than me and I am not other than emptiness’. Now let’s look at the ‘Stages of Meditation’.”

His Holiness remarked that ‘Stages of Meditation’ has a special significance for Tibetans. It was requested and composed in Tibet at a time when Tibet was a powerful empire. Shantarakshita had ordained the first monks and established Samye as the first monastery. Within that were departments of translation, celibacy, meditation and so forth. Chinese monks in the department of meditation began to teach that study was unnecessary and meditation alone was sufficient to attain Buddhahood. Shantarakshita’s distinguished disciple Kamalashila was invited to challenge this. He took the Chinese monks on in debate and won. The three volumes of ‘Stages of Meditation’ were written as a consequence.

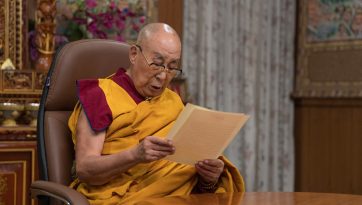

After reporting that he had received an explanation of the entire work from Sakya Abbot Sangye Tenzin, who in turn had heard it from a Khampa Lama at Samye, His Holiness began to read the text, covering the initial sections – What is mind? Training the mind, Compassion, Developing equanimity, the root of loving-kindness and began to read Identifying the nature of suffering.

After lunch, His Holiness met with about 300 students from schools in Nubra and 200 monks and nuns who had taken part in the Great Summer Debate. He greeted them all and expressed the hope that the 21st century would be different from the century that had gone before, marked as it was by tremendous violence. He encouraged the young people to understand that with determination and a clear vision it would be possible to create a more peaceful, happier era, but it would require people to think not just of their own well-being, but the welfare of humanity as a whole.

A number of schoolgirls asked questions. The first was about how much merit was entailed in achieving the path of preparation. She clarified that what prompted her to ask was a verse in ‘Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life’ that mentions that merit collected over 1000 aeons could be destroyed by one moment of anger. His Holiness made plain that the verse in question refers to a lower bodhisattva’s anger with a higher bodhisattva. An ordinary person’s anger is negative, but is not so destructive.

Another student’s question about observing the five precepts of a layperson as a student prompted His Holiness to point out that, barring the last, which concerns wrong view and is to be interpreted by each faith according to their own tradition, all religions observe avoidance of the ten unwholesome deeds.

A question about coarse and subtle impermanence elicited a reply that to be born, to live and eventually to die is an example of the first. Subtle impermanence involves momentary change. It is implicit in the cause of the thing rather than being the result of any additional intervention. His Holiness remarked that you can see momentary change taking place through a microscope. Another student wanted to know the Buddhist interpretation of the ‘big bang’. His Holiness’s answer mentioned periods of arising, abiding and destruction and observed that scientists are only concerned with the most recent ‘big bang’, but it’s not unreasonable to believe that others have taken place before it.

A monk raised the issue of the existence or otherwise of Mount Meru. His Holiness asked him if he would agree that there was no elephant in front of him. The monk agreed that he couldn’t see one, but suggested that sometimes we say that not being able to see something doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Ganden Trisur, Rizong Rinpoche pointed out that Mt Meru’s non-existence has implications for other locations such as the celestial realm of Tushita.

Noting that it is usual to say that there is no place for caste discrimination in Buddhism, a nun sought His Holiness’s reaction to a question in the ordination procedures that asks – “Are you the son or daughter of a blacksmith?” His Holiness responded that he had never seen it, so had nothing to say, but recalled that the Buddha had advised a king to disregard Upali’s origins in a barber’s family and to pay him respect on grounds of his knowledge and practice.

As the meeting came to a close, His Holiness thanked the students for their meaningful questions and encouraged them to pay more attention to the classic texts of Indian masters such as the pandits of Nalanda. He added that Muslims could also benefit from learning more about logic and epistemology. Both areas of study can best be done in the Tibetan language, which Ladakhis are able to read despite having their own spoken dialect.

His Holiness will continue to teach ‘Stages of Meditation’ and Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas’ tomorrow.

Source: https://www.dalailama.com/news/2017/teaching-stages-of-meditation-and-thirty-seven-practices-of-bodhisattvas-at-disket